Symphony Preview: Critical failure

By

This weekend (March 29-31) Jakub Hrusa leads the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra in three works by well-established composers that were nevertheless greeted with a mixture of bafflement and hostility when they were first performed. Not surprisingly, history has since vindicated the composers.

|

| Béla Bartók in 1927 |

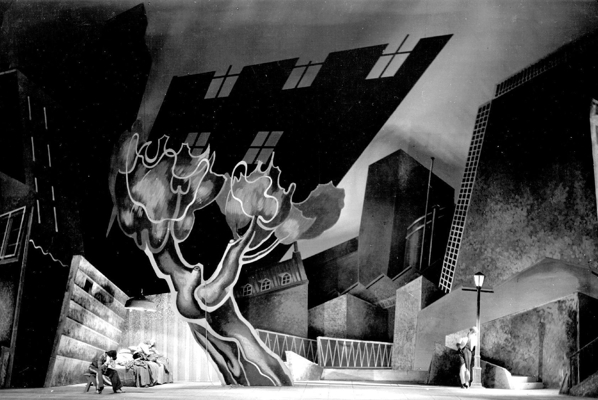

The concerts open with a suite from Béla Bartók's ballet "The Miraculous Mandarin." First performed in Cologne, Germany, in November 1926, the ballet's sordid and violent story so outraged local audiences and religious leaders that the mayor, Konrad Adenauer (who would later be Germany's first post-WW II chancellor), had it banned. After a subsequent and equally controversial performance in Prague (the last one Bartók would see in his lifetime), the ballet was not staged again until Aurel von Miloss choreographed a production in Milan (at Teatro alla Scala) in 1942.

What was all the fuss about? Thomas May has a synopsis in his program notes and there's an even more detailed one at Wikipedia, but essentially the story concerns a trio of thugs who force a young woman to lure unsuspecting rubes to an upstairs room where they're robbed, beaten, and tossed out into the street. The first two victims, an old man and a student, are easily dispatched, but the third--the wealthy Chinese man of the title--proves to be much tougher. The criminals try to kill him by suffocation, stabbing, and hanging, but he refuses to die until the woman finally embraces him, at which point he bleeds and expires.

Not exactly family friendly stuff. Also rather Freudian. Choreographer Attilla Bongar has posted a YouTube video of his version of the ballet and while the video quality is not great, it does give you a pretty good idea of what the action looks like.

The music Bartók wrote was appropriately aggressive and discordant. In an article for "The Listeners Club", Timothy Judd calls it "one of the scariest pieces ever written" and quotes the composer (in 1918) predicting that it would be "hellish music." Mr. Judd goes on to quote the musicologist and Bartók biographer József Ujfalussy on the way in which the ballet was a reflection of the post-WW I zeitgeist:

European art began to be populated by inhuman horrors and apocalyptic monsters. These were the creations of a world in which man's imagination had been affected by political crises, wars, and the threat to life in all its forms... This exposure of latent horror and hidden danger and crime, together with an attempt to portray these evils in all their magnitude, was an expression of protest by 20th-century artists against the...obsolete ideals and inhumanity of contemporary civilization. [Bartók] does not see the Mandarin as a grotesque monster but rather as the personification of a primitive, barbaric force, an example of the 'natural man' to whom he was so strongly attracted.

A quick glance at my news feed suggests that, if Mr. Ujfalussy is correct, this may be music whose hour (like that of Yeats's rough beast) has "come round at last."

|

| Tchaikovsky, aged 52. Photographed by Alfred Fedetsky in Kharkov, 14/26 March 1893 wiki.tchaikovsky-research.net |

Up next is Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto in D Major. Although wildly popular these days, the concerto was originally dismissed as "unplayable" by St. Petersburg Conservatory violin professor Leopold Auer (to whom it was originally dedicated and who was supposed to play it at its premiere). Tchaikovsky's colleague Adolf Brodsky would replace Auer as both the first performer and the dedicatee.

I wrote at some length back in 2015 about the concerto and the oddly hostile reactions it got from clueless critics, so I won't repeat myself here. The bottom line is that it's now a beloved part of the repertoire and never fails to be a crowd pleaser.

The violin soloist this weekend will be Karen Gomyo, who has gotten her share of critical praise over the years. "A first-rate artist of real musical command, vitality, brilliance and intensity," wrote John Van Rhein at the Chicago Tribune in 2009, while the Cleveland Plain Dealer's Zachary Lewis called her "captivating, honest, and soulful, fueled by abundant talent but not a vain display of technique" in 2011. Reviewing her performance of works by Chausson and Sarasate here in 2017, I praised her technical proficiency and intense artistic focus. I look forward to seeing what she does with Tchaikovsky's so-called "unplayable" masterpiece.

Shostakovich's Symphony No. 9, which concludes this weekend's concerts, actually got some decent notices when it was first performed on November 3, 1945, by the Leningrad Philharmonic under Yevgeny Mravinsky, who conducted the world premieres of several other Shostakovich symphonies. His fellow composer Gavriil Nikolayevich Popov, for example, reacted to it this way (cited in "Shostakovich: A Life" by Laurel E. Fay):

Transparent. Much light and air. Marvelous tutti, fine themes (the main theme of the first movement -- Mozart!). Almost literally Mozart. But, of course, everything very individual, Shostakovichian... A marvelous symphony. The finale is splendid in its joie de vivre, gaiety, brilliance, and pungency!!

That opinion didn't last. As conductor Mark Wigglesworth writes on his blog, "Stalin was incensed when he heard the piece." Coming immediately after the conclusion of the Great Patriotic War (World War II to the rest of us) he had expected a grand heroic apotheosis, not "literally Mozart." As Mr. Wigglesworth notes, the winds of opinion quickly changed:

Within a year of its première in 1945, Soviet critics censured the symphony for its 'ideological weakness' and its failure to 'reflect the true spirit of the people of the Soviet Union.' One described it as 'old man Haydn and a regular American sergeant unsuccessfully made up to look like Charlie Chaplin, with every possible grimace and whimsical gesture.' Others, in more private circles, understood 'its timely mockery of all sorts of hypocrisy, pseudo-monumentality, and bombastic grandiloquence.' It was banned for the remainder of Stalin's life and not recorded until 1956. Nor was the work particularly well received in the West. According to an American critic, 'the Russian composer should not have expressed his feelings about the defeat of Nazism in such a childish manner.'

|

| Shostakovich in 1945 |

In all fairness, Shostakovich might have been partly responsible for raising false expectations. "Undoubtedly like every Soviet artist," he declared on the occasion of the 27th anniversary of the revolution in 1944, "I harbor the tremulous dream of a large-scale work in which the overpowering feelings ruling us today would find expression. I think the epigraph to all our work in the coming years will be the single word 'Victory'."

He even went so far as to compose the first several minutes of that planned celebratory work early in 1945. As scholar Olga Digonskaya writes, fellow composers who heard him perform it described the fragment as "powerful, energetic and triumphant." Dissatisfied, he set the fragment aside, and by the summer his thoughts had completely changed. Running under a half hour, the final version of the Symphony No. 9 is a brisk, and (at least in the first movement) openly comic work with (as Mr. May writes in his notes) "a shockingly (to those who wanted it) unheroic finale."

If you want to listen to the complete symphony in advance, let me recommend a recording by the WDR Symphony on YouTube that includes a synchronized display of the score. Note the many prominent solos for instruments that don't always get them like the piccolo, bassoon, and trombone.

This week's guest conductor, Jakub Hrusa, was born in Brno, Czechoslovakia in 1981. He studied paino and trombone before taking up the baton at the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague. He's Chief Conductor of the Bamberg Symphony, Principal Guest Conductor of the Philharmonia Orchestra, and Principal Guest Conductor of the Czech Philharmonic. Recent debuts include guest appearances with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio Symphony, Orchestre de Paris, and NHK Symphony.

The Essentials: Jakub Hrusa conducts the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, along with violinist Karen Gomyo, Friday and Saturday at 8 pm and Sunday at 3 pm, March 29-31. The concerts take place at Powell Symphony Hall, 718 North Grand in Grand Center.