Symphony Preview: Getting with the program

By

This weekend, four of the five works Stéphane Denève and the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra (SLSO) will perform are unabashedly descriptive--what they used to refer to as "program music" in Music Appreciation classes. The fifth, by way of contrast, is by a guy who did his level best to insist that he only wrote "absolute" music.

|

| Composer John Adams Photo: Vern Evans |

As I learned back when they still routinely taught music in the public schools (yes, I am a geezer) the difference between "absolute" music (your basic sonatas, concertos, symphonies, etudes, et al.) and "program music" (the "symphonic poem" and anything else with a descriptive title) was that the former had no specific external reference while the latter was inspired by or descriptive of something non-musical. That "something" can encompass anything from a literary classic (Schumann's "Manfred Overture") to a painting (Rachmaninoff's "Isle of the Dead") to a mountain-climbing expedition (Richard Strauss's "Alpine Symphony")--all of which have been heard on the Powell Hall stage recently.

The concerts this weekend open a pair of short pieces of "program music" that involve being transported. Not in the emotional sense of being swept away, but in the far more mundane sense of being taken from one place to another by a machine.

Up first is John Adams's "Short Ride in a Fast Machine" from 1986. The work is described as a "fanfare for orchestra" on the composer's web site, where Mr. Adams explains the title by posing a question: "You know how it is when someone asks you to ride in a terrific sports car, and then you wish you hadn't?"

Running around four minutes, "Short Ride in a Fast Machine" is a headlong rush down narrow country roads. The woodblock, clarinets, trumpets, and synthesizer keep up a fast, steady beat while the rest of the orchestra races ahead, holding on for dear life. In his notes on Adams's web site, Michael Steinberg describes the piece as "joyfully exuberant," but to me it has always had a "how the hell do you stop this thing?" subtext.

And, yes, it's also great fun.

|

| Arthur Honegger in 1928 By Agence de presse Meurisse - Bibliothèque nationale de France, Public Domain, Link |

Up next is Arthur Honegger's "Pacific 231," a piece inspired by the composer's love of train travel. "I have always loved locomotives passionately," he once noted. "For me they are living creatures and I love them as others love women or horses." Originally titled simply "Mouvement Symphonique No. 1" (the first of a series of three), the title "Pacific 231" was added later as an acknowledgement of its inspiration in the many hours he spent in train travel in his youth.

This is music so vividly descriptive of the experience of riding on a powerful locomotive that it eventually became the basis of a 1949 film that featured footage of locomotives synched up with the music. Not that the visuals are really necessary; you can hear the massive engine start up and begin to gather speed at the beginning in the percussion, low strings, and brasses. Soon other instruments join in as the momentum increases. The city and suburbs swirl past until you're flying through open fields with the woodwinds and higher strings. Finally there's a massive orchestral crash as the air brakes kick in and the mighty 231 slows to a stop at your destination.

If you have ever ridden on a high-speed intercity train of the type they have in Europe, you'll recognize the feeling.

|

| Guillaume Connesson Photo by Fanny Houillon |

The inspiration for the next work, a saxophone concerto by Guillaume Connesson, is also a "train," but only in the homophonic sense. Titled "A Kind of Trane," it's a tribute to the virtuosity and frenetic energy of the late jazz saxophonist John Coltrane.

First performed at the World Saxophone Congress in 2015, "A Kind of Trane" is scored for two saxophones (soprano in the first and third movement and alto in the second) and, in fact, was played by three different soloists at its premiere. As Tim Munro writes in this week's program notes, the first two movements are inspired by specific Coltrane albums--"A Love Supreme" and "Ballads," respectively, while the final, wildly virtuosic movement (titled "Coltrane on the Dance Floor") "contrasts the freedom of Coltrane's playing with what he thinks is the 'robotic' nature of today's dance music."

That last movement really is a killer, demanding pretty much everything a player can give. Watch the performance by Nicholas Prost, who first performed it at the 2015 premiere, to see what I mean. The music builds to a wild climax until the solo line collapses into a few quiet toots, as though the exhausted Coltrane has collapsed into a chair and reached for a stiff drink.

For this performance, one soloist will tackle all three movements. Fortunately, that one performer is Tim McAllister, who has displayed the kind of superhuman virtuosity this music clearly needs in previous appearances with the SLSO.

|

| Albert Roussel in 1913 Public Domain, Link |

In contrast to those last three pieces, the next item on the bill of fare is Albert Roussel's Symphony No. 3 in G minor, Op. 42, from 1930. It has no programmatic subtitles. Indeed, Roussel, in a 1928 interview, declared that his goal as a composer was "to achieve...a music that is entirely self-contained, music that aims to free itself from any pictorial or descriptive element and completely removed from any geographical connection."

Did he succeed with his third symphony? There are certainly no descriptive titles to any of the four movements but, least to me, they all conjure up some fairly specific images.

The pounding rhythms of the Allegro vivo first movement, for example, suggest the kind of mechanical precision that characterizes the 1924 "Ballet Mécanique" of his contemporary George Antheil (an American composer living in Paris at the time), although that driving motion is tempered by lyrical passages. The Adagio second movement is a sometimes unsettling mix of the eerie and ominously dramatic. To me, it conjures up memories of the Catacombs and/or Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, but your mileage could vary.

The third and fourth movements, in sharp contrast, suggest wild nights at a rowdy cabaret in Montmartre or maybe the more unbuttoned Quartier Pigalle, home of the Moulin Rouge. Or a lively jazz club anywhere, really.

That said, your reaction might be completely different. Which would, of course, reinforce Roussel's insistence that the Symphony No. 3 isn't "about" anything in particular.

|

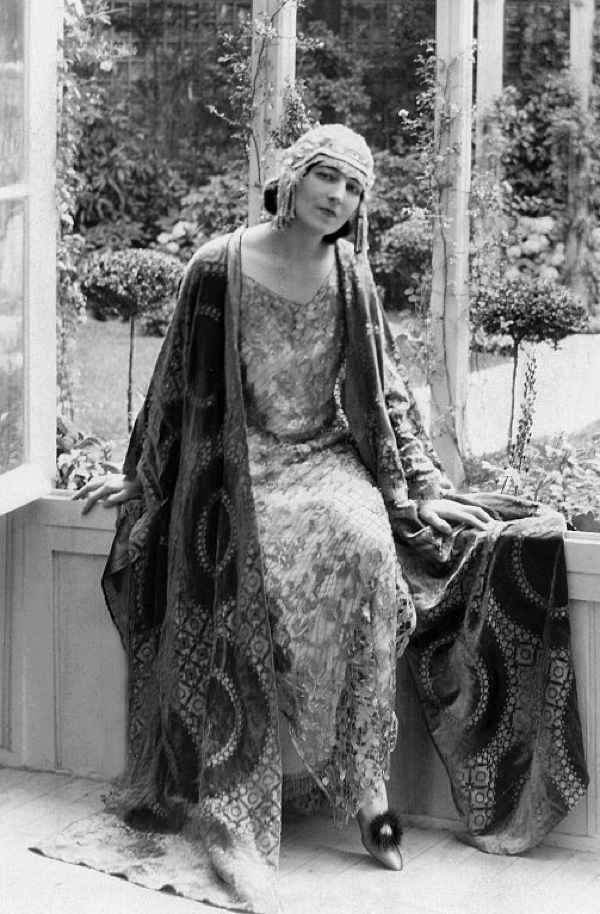

| I forgot to mention her, didn't I? officialboderek.com |

Wrapping things up is one of the most popular orchestral works ever written and certainly the best-known thing Maurice Ravel ever wrote: "Boléro." Composed originally on commission for the dancer Ida Rubinstein, "Bolero" was first performed by her at the Paris Opéra on 22 November 1928, with choreography by Bronislava Nijinska and designs by Alexandre Benois.

The scenario, as printed in that first program, describes a wild night in a Spanish tavern that gets wilder when a female dancer leaps on to a table as "her steps become more and more animated." The late New York Times music critic Louis Biancolli (quoted in the 1962 edition of Julian Seaman's "Great Orchestral Music: A Treasury of Program Notes") goes into greater detail, describing an increasingly erotic bacchanal, which ends in a knife-wielding brawl.

There will be no weapons at Powell Hall this weekend, fortunately, so you will be able to enjoy Ravel's Greatest Hit in safety.

There are many more fascinating facts to be had about "Boléro," including its sexual subtext. Actor/writer Albert Brooks had some fun with that aspect of the work on his subversively brilliant 1975 LP "A Star is Bought." Happily, that album is still available in digital form from Amazon and is mandatory listening for anyone who enjoys a good, smart laugh.

The Essentials: Stéphane Denève conducts The St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, along with saxophonist Timothy McAllister on Friday at 10:30 am and 8 pm and Saturday at 8 pm March 6 and 7. Performances take place at Powell Symphony Hall in Grand Center.