Rising to the occasion: Mahler's 'Resurrection' for Easter

By

Well, here it is Easter week. Last Sunday was Palm Sunday, the day Christians celebrate Jesus's entry into Jerusalem only a few days before his crucifixion. I expect that means many of you classical music fans out there might be listening to some works often associated with the season.

If so, you have plenty of options, ranging from reverential pieces like Bach's "Easter Oratorio" (BWV 249) to Haydn's "The Seven Last Words of Our Savior on the Cross" or even to Rachmaninoff's titanic "All-Night Vigil," Op. 37. Or you can go the more celebratory route with Rimski-Korsakov's "Russian Easter Festival Overture."

|

| Patti Smith's Easter By Source, Fair use, Link |

There are numerous settings of "Stabat mater", the 13th-century hymn that describes Mary's suffering during the crucifixion, from Josquin des Prez in the mid-15th century to James MacMillan (whose music will be included in the 2020-2021 St. Louis Symphony Orchestra schedule). And, of course, Patti Smith's "Easter".

OK, just kidding about that last one, although "Because the Night" should really be on everyone's Top 10.

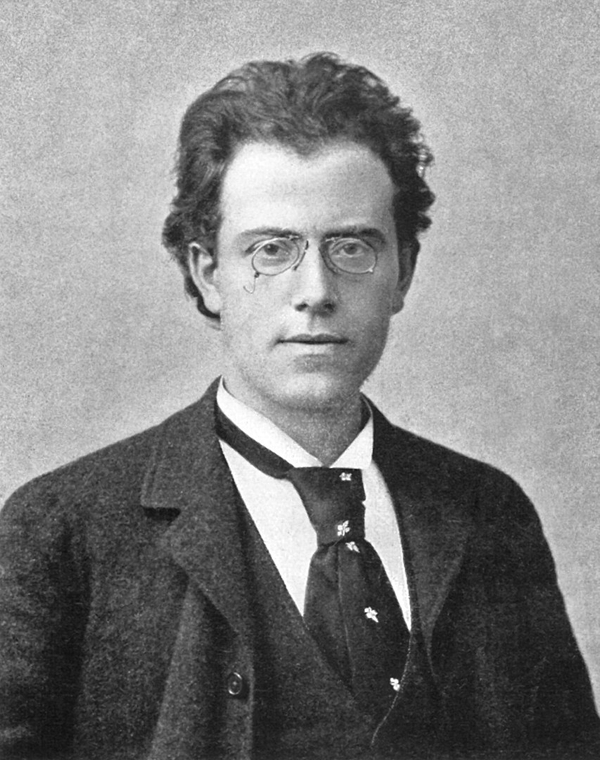

My top choice for the season, though, is Mahler's Symphony No. 2 ("Resurrection"), the 1895 premiere of which launched the composer's career.

According to musicologist Donald Mitchell, Mahler once told Sibelius that a symphony "must be like the world. It must embrace everything." His "Resurrection" Symphony takes that "one stop beyond" to embrace not only the world but also what comes after the world has been left behind. Death, rebirth, transcendence--it's all here and delivered with that dramatic punch that characterizes Mahler's best work.

The "Resurrection" had a long gestation period. Mahler composed the grandly tragic first movement--which he titled Todtenfeier ("Funeral Rite")--in 1888, shortly after the completion of his popular Symphony No. 1. Indeed, as Richard Freed points out in program notes for the National Symphony Orchestra, the composer originally intended this movement as "a direct sequel to his First Symphony, representing the funeral of the hero celebrated as a young man in that just-completed work."

|

| Contemporary characterture of Mahler conducting his Symphony No. 1 |

In 1889, during his tenure as director of the Budapest Opera, he began work on the sweetly nostalgic second movement, with its reflection of earthy joys left behind, but didn't manage to finish it until 1893, when he had relocated to Hamburg. There, he also wrote the witty scherzo that became the symphony's third movement. Based on Mahler's earlier setting of a poem from the collection of folk poetry "Das Knaben Wunderhorn" ("The Boy's Magic Horn") about St. Anthony trying to preach to fishes--who, like humans, listen politely and then and go on their merry way--it becomes a metaphor for the endless whirl of daily existence.

At the same time Mahler wrote another "Wunderhorn" song, "Urlicht" ("Primal Light") which would become the basis for the mysterious fourth movement. It represents, in Mahler's words, "the soul's striving and questioning attitude towards God and its own immortality."

The grand final movement, with its overwhelming depiction of the end of the world and the final spiritual rebirth of all things, didn't take shape until 1894 when Mahler attended the funeral of Hans von Bülow, the renowned pianist and conductor who was a major figure on the 19th-century German musical scene. At the funeral, the chorus began to intone the first words of Friedrich Gottlob Klopstock's "Resurrection Ode"):

Rise again, yes, you will rise again,

My dust, after brief rest!

Immortal life! Immortal life

Will He, who called you, grant you.

As Mahler wrote in an 1897 letter to Arthur Seidl "It flashed on me like lightning, and everything became plain and clear in my mind! It was the flash that all creative artists wait for--"conceiving by the Holy Ghost!" He fleshed out Klopstock's original with lyrics of his own (see below) and the symphony was finally born.

The work was the most popular of Mahler's symphonies during his lifetime and it was voted the fifth most popular symphony of all time by a worldwide poll of high-profile conductors conducted by the BBC Music Magazine in 2016.

| The SLSO assembles for the Mahler 2nd in 2019 |

In program notes for the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra's performance of the "Resurrection" last September, Maestro Denève articulated the work's universal appeal quite well. "Maybe the 'Resurrection' is the most global of Mahler's symphonies," he observed. "It is beyond religion. He had lost his mother, his father, his sister. At the end of the Second Symphony, the god that offers the possibility to arise, to be immortal, is a god that does not judge. It is about love. The way we will save ourselves is love."

If that sounds rather unlike the angry, hyper-judgmental religion of some believers these days, perhaps it's because Mahler's own faith has never been entirely clear. An Austrian Jew who converted to Catholicism out of professional expediency, Mahler has always, to my ears, shown a kind of joyous pantheism in his music that transcends the crabbed limitations of dogma. You hear it most prominently in his Symphony No. 3, but also in those lines that Mahler added to Klopstock's originals in the triumphal, ecstatic finale of the "Resurrection" (translation from the SLSO program):

O believe, my heart, believe:

Nothing will be lost to you!

Yours, yes, yours is what you longed for,

Yours what you loved,

What you fought for!

O believe:

You were not born in vain!

You have not lived in vain, nor suffered!

All that has come into being must perish!

All that has perished must rise again!

Cease from trembling!

Prepare to live!

O Pain, piercer of all things!

From you I have been wrested!

O Death, conqueror of all things!

Now you are conquered!

With wings I won for myself,

In love's ardent struggle,

I shall soar upwards

To that light which no eye has penetrated!

I shall die so as to live!

Rise again, yes, you will rise again,

My heart, in the twinkling of an eye!

What you have conquered,

Will bear you to God!

|

| Normal Lebrecht By Abigail Lebrecht en:wiki, Public Domain Link |

This God doesn't build walls. He doesn't have someone sitting at the gates of heaven to weigh souls. He's not interested in seeing anyone roast in hellfire. He's just welcoming back the part of himself that lives in everyone and everything. As Norman Lebrecht writes in "Why Mahler?: How One Man and Ten Symphonies Changed Our World" (Anchor Books, 2010), "Mahler's Resurrection Symphony is deliberately Christless...A century will pass before Pope John Paul II, hearing the symphony in the Vatican in January 2004, speaks of its quest for 'a sincere reconciliation among all believers in the one God,' erasing--as Mahler intended--the artificial divisions of doctrine."

As you may have gathered from the preceding, the "Resurrection" Symphony has long been a favorite of mine, going back to my first encounter with the classic Otto Klemperer recording from early 1960s. A kind of Mahler multivitamin, the "Resurrection" contains all the key elements of the Viennese master's work: moments of chamber-music delicacy alternating with massive orchestral outbursts, vulgar marches, lilting Ländler, a darkly comic scherzo, and passages of sublime beauty, and, of course, that overwhelming final movement. And yet, in the musical equivalent of alchemy, Mahler's sense of architecture somehow transmutes it all in to a single, unified work that brilliantly encompasses the themes of death, rebirth, and transcendence.

Done well, the work's final glorious moments of spiritual rebirth never fail to move one to tears.

If you'd like a more detailed breakdown of the work, there's quite a good one at the web site of the Utah Symphony Orchestra, whose complete Mahler symphony cycle under the baton of Maurice Abravanel was one of the first to appear on LPs back in the 1960s. For a lighter point of view, there's a droll article at Britain's commercial classical music station Classic FM that includes video snippets of great conductors going into near-orgasmic states of ecstasy conducting the work's final moments. It's irreverent but not inaccurate.

|

| Leonard Slatkin Photo courtesy of the SLSO |

As for recordings of the "Resurrection," there are so many out there displaying such a wide interpretive range that it's difficult to make a recommendation. My own favorite is the one Leonard Slatkin recorded with our own St. Louis Symphony Orchestra and Chorus (back when Thomas Peck was the chorus director) in 1983. I saw this performance live and was blown away by it. Telarc's digital recording does a remarkably good job of capturing the wide dynamic range of this performance.

Over at The Gramophone, Edward Seckerson regards Vladimir Jurowski's 2011 recording with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir as a "the most illuminating to have appeared on disc in a very long time." At NPR, Ted Libbey praises Leonard Bernstein's New York Philharmonic recording for it's "apocalyptic vision." "This is the Resurrection taken to the limit, and then well beyond, he writes. " It may not be a reading to everyone's liking, but it is certainly an experience, and there's no question of the performers' commitment."

And, of course, the late Bruno Walter's 1958 recording with that same orchestra has the advantage of being the work of a man who knew Mahler personally and was his protégé. It has the disadvantage of being somewhat dated sonically.

Regardless of which recording you listen to (and I haven't even touched on the plethora of them available for free on YouTube), I can't think of a better way for the classical music lover to spend part of their stay-at-home Easter Sunday than to curl up with a decent wine and savor Mahler's apocalyptic and inspiring vision of life and death.