Symphony Preview: Who's on first

By

This Friday and Saturday, January 7 and 8, Stéphane Denève conducts the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra in a program of firsts: The first symphony of Brahms, the first published piano concerto of Beethoven, and the first St. Louis performance of Detlev Glanert’s “Brahms-Fantasie”—a work inspired by the Brahms symphony.

[Preview the music with my commercial-free Spotify playlist.]

|

| Detlev Glanert boosey.com |

Detlev Glanert, whose music opens the program, is not an unknown name here. The orchestra performed his Richard Strauss homage/pastiche "Frenesia" ("Frenzy") under David Robertson in 2015 and his "Vier Präludien und ernste Gesänge" ("Four Preludes and Serious Songs") in 2014. The latter is yet another Brahms-inspired work, being an arrangement of the earlier composer’s op. 121 "Four Serious Songs" interspersed with orchestral preludes by Glanert.

If that makes you think Glanert might have a high regard for Brahms, you’d be right. The two composers share a hometown (Hamburg) along with what Glanert calls "a specific North German tradition, in which I believe myself to be connected with Brahms, to do with a melancholy in his pieces, with a certain severity." It’s not surprising, then, that Glanert was one of four composers commissioned by the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra to write short companion pieces for each the four Brahms symphonies. Glanert’s companion piece for the Symphony No. 1 in C minor, op. 68, was the last to be presented, getting its world premiere by Donald Runnicles and the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra in Glasgow in March 2012.

Usually, I’m able to find performances of works that have been around for few years online, but no such luck this time around (hence its absence from my Spotify playlist), so just like most of you, I’ll be hearing the “Brahms-Fantasie” for the first time this weekend. Fortunately, Thomas Tangler provides a fairly detailed analysis at the Boosey and Hawkes web site. The “Fantasie” is subtitled “Heliogravure for orchestra” which, according to Tangler, refers to “a nineteenth-century technique, no longer common today, in which photographs are painted over by means of a chemical process—an original material thus appears as something transfigured and ‘re-kneaded,’ remains present in its original form and is nevertheless something new through the intervention of an artist.”

|

| Beethoven in 1803 Painted by Christian Horneman |

In short, old wine in new bottles—probably with a distinct 21st-century tang.

Up next is the Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, Op. 15, by Beethoven. It's officially his Piano Concerto No. 1 because it was the first of his five concerti to be published, but it was actually his second essay in the form, dating from 1797—two years after the Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major. It is, as a result, more richly orchestrated, more sophisticated, and a bit less derivative of Mozart and Haydn than the B-flat major concerto. I think Haydn’s influence is most apparent in the Allegro scherzando finale, both in the jollity of the music and in the fact that it’s a rondo—a favorite form of the composer. The noble opening theme of the first movement, though, strikes me as pure Beethoven.

This brings us to the final item on the program, Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 in C minor, op. 68.

Although Brahms was an early bloomer as a composer—he reportedly wrote his first piano sonanta at the age of 11—he got off to a late start as a symphonist. His Symphony No. 1 wasn't performed until 1876 (when Brahms was 43) and wasn't published in final form until the following year. "Part of the problem," wrote Larry Rothe in program notes for the San Francisco Symphony, "was that Brahms was such a harsh critic of his own work. He honed his material until he was satisfied, and he held himself to tough standards.” Worse yet he ”was intimidated by Beethoven. 'You have no idea what it's like to hear the footsteps of a giant like that behind you,' he said."

You can, I suppose, hear those footsteps in the steady tread of the tympani that forms the basis of the magisterial opening of the first movement, but even so it seems astonishing that music projecting such assurance could have sprung from the brain of a man consumed with self-doubt.

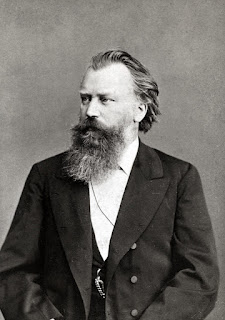

|

| Brahms in 1885 Photo by Fritz-Luckhardt |

The other movements are equally impressive. A lyrical Andante is next—featuring a graceful trio for oboe, violin, and horn—followed by a terpsichorean third movement marked un poco allegretto e grazioso. And then Brahms caps it all with a highly charged finale which, as Tom Service writes in The Guardian, “crowns the work's dramatic trajectory.”

The notion that the final movement should carry the most dramatic weight in a symphony was not new—Beethoven did it back in 1808 with his famous Symphony No. 5—but even so (as Service notes in his article) it was a departure from a long-standing 19th-century tradition.

Brahms might have gotten a late start at the symphony game, but maybe that’s one reason why it’s such a robust start. Most first symphonies unmistakably come from a place of youthful experimentation. The Brahms First comes from a place of mature confidence. “By the time the symphony was premiered,” writes Tim Munro in this week’s program notes, “Brahms was a professional success. His journey from obscurity to fame had been long, and the First Symphony had been his private companion. Now it would belong the world.”

The Essentials: Stéphane Denève conducts the SLSO and piano soloist Shai Wosner (substituting for the originally scheduled Lars Vogt) in the Symphony No. 1 by Brahms, Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 1, and Detlev Glanert’s 2012 “Brahms-Fantasie.” Performances are Friday at 10:30 am and Saturday at 8 pm, January 7 and 8 at Powell Symphony Hall in Grand Center.

Note that due to the sudden sharp increase in COVID-19 cases, concessions will not be available and there will be no eating or drinking allowed in the foyer or lobby spaces. Masks must be worn at all times, and a (1) vaccination card or negative COVID-19 test and (2) a photo ID are required for entry.