Symphony Preview: Myth management

By

My wife and I have become dedicated travelers over the last couple of decades, but we can't hold a candle to the French composer Camille Saint-Saëns. Over the course of his long (1835-1921) and prosperous life, his peregrinations took him all over Europe as well as to England, the United States, and even (in 1896) to Algeria and Egypt.

[Preview the music with my commercial-free Spotify playlist.]

|

| Saint-Saën in 1900 By Petit, Pierre (1831-1909) Photographer Restored by Adam Cuerden |

A musical souvenir of the latter trip closes the first half of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra (SLSO) concerts this weekend (March 11-13) as pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet joins Stéphane Denève for the Saint-Saëns Piano Concerto No. 5 in F major, op. 103 (“Egyptian”). As Michael Steinberg writes in his program notes for the San Francisco Symphony, the concerto picked up its nickname from the composer's own comments about the piece, which was written during a winter trip to Luxor:

Of the second movement, Saint-Saëns himself wrote that "it takes us, in effect, on a journey to the East and even, in the passage in F-sharp, to the Far East." First comes an extended introductory section, much of it like recitative, and then the music settles into a pleasant and serene song for piano and strings. Saint-Saëns said that it was "a Nubian love song which I heard sung by boatmen on the Nile as I myself went down the river in a dahabieh."

The sound of that second movement is so exotic that pianist Steven Hough once wrote a tongue-in-cheek explanation of how to achieve it for the April Fool's Day, 2012, edition of his blog at the Daily Telegraph. It's worth reading.

The "Egyptian" concerto hasn't been heard on the Powell Hall stage since 2016, by the way, so this is a rare opportunity for local classical music lovers to catch it live.

Preceding the Saint-Saëns concerto, though, we’ll have a work making its world debut: the “Goddess Triptych” by contemporary (b. 1969) American composer Stacy Garrop. Written for the SLSO and commissioned by the League of American Orchestras, the work was written in 2020 but will be performed for the first time ever this weekend, so I can’t tell you what to expect from it. Your best bet is just to read what the composer herself has to say about it on her web site.

That said, you can get an idea of Garrop’s eclectic style from her “Mythology Symphony,” the first movement of which is part of my Spotify playlist. At just under 13 minutes it’s almost exactly the same length as the “Goddess Triptych,” so it will give you at least some notion of what you’ll hear.

|

| Stacy Garrop Photo: Darrell Hoemann Photography |

After intermission, we get a double helping of ballet: Paul Dukas’s one act “La Péri” (including its famous brass fanfare) and a suite from Stravinsky’s “L'Oiseau de feu” (“The Firebird”). The two ballets were composed within a year of each other—“La Péri” in 1911 and “The Firebird” in 1910—and were both originally scheduled to be premiered by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Paris.

Unfortunately Diaghilev thought Ukrainian dancer Natalia Trouhanova, who was to play the title role in Dukas’s ballet, wasn’t up to the part and the Ballet Russes production was cancelled. The result, as James M. Keller writes in notes for the San Francisco Symphony, was a bit of a scandal. “The press went berserk, Trouhanova went into a sulk, and Dukas withdrew his score.” Trouhanova eventually emerged from her sulk and produced a “danced concert” version of the ballet in 1912 at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris with Dukas at the podium. This was, happily, a hit. “To what can we attribute the deep impression caused by this work, which is undoubtedly a masterpiece?” asked Robert Brussel in “Le Figaro.” “I believe that it is an element that cannot be measured, the only one that mediates about perfect beauty: poetry.”

Based on Persian folklore, “La Péri” is the story of prince Iskender’s theft of the Flower of Immortality from a sleeping peri (a winged female fairy) and why this turns out to be an unwise decision on his part. The music is lush and suffused with the fashionable perfume of Orientalism. The same scent is discernable in other works from around the same time, including Richard Strauss’s “Salome” (1905) Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Le coq d’or” (1909), Florent Schmitt’s “La tragédie du Salomé” (the 1912 expansion of which shared the bill with the “La Péri” premiere) and, of course, “The Firebird.”

The first in what turned out to be a series of successful collaborations between the composer and impresario Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, "Firebird" contains hints of the upheaval Stravinsky would generate with "Rite of Spring" and "Les Noces" but also pays homage to the work of more conservative Russian composers like the aforementioned Rimski-Korsakov and even, in the final moments of the “Infernal dance” number, Ravel.

Stravinsky owed the opportunity to write "Firebird" to the laziness of his former teacher at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, Anatoly Lyadov. Diaghilev originally commissioned Lyadov to write the score but (according to Verna Arvey in "Choreographic Music") when, after months of waiting, Diaghilev went to see Lyadov to view his progress, the composer said, "it won't be long now. It's well on its way. I have just bought the ruled paper."

Soon Lyadov was out, and Stravinsky was in.

|

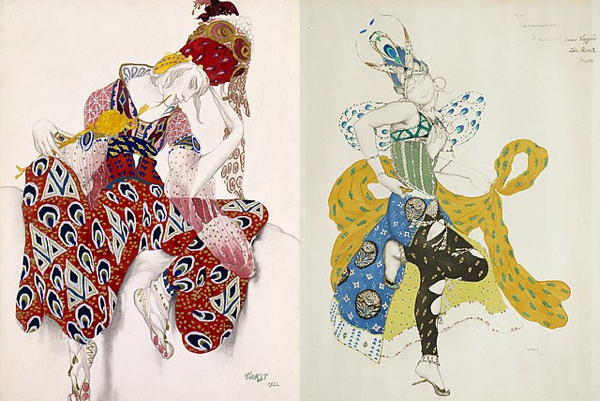

| Costume sketch for The Firebird by Leon Bakst en.wikipedia.org |

The massively successful premiere of "Firebird" put Stravinsky on the map, musically speaking, and it remains one of his most popular works. It also made the composer an instant celebrity, rubbing shoulders with the likes of Marcel Proust, André Gide, and Sarah Bernhardt. Stravinsky prepared three concert suites from the ballet: one in 1910, a second in 1919, and the third in 1945. The final suite increased the number of selections from five to ten and the running time from 20 minutes to 30 but reduced the size of the orchestra. This weekend we’ll be hearing the shorter 1919 suite but with the 1945 orchestration.

Interested in seeing a complete performance of the ballet? Fortunately, there are two (that I know of) on YouTube. I put them together in a playlist for your convenience. And, of course, there’s a wonderfully excessive recording of the 1919 suite by Leopold Stokowski in my Spotify playlist.

The Essentials: Stéphane Denève conducts the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra and soloist Jean-Yves Thibaudet in Stacey Garrop’s “Goddess Triptych,” Saint-Saëns’s Piano Concerto No. 5 (“Egyptian”), Dukas’s “La Péri” ballet, and a suite from Stravinsky’s “The Firebird.” Performances are Saturday at 8 pm and Sunday at 3 pm, March 12 and 13. Saturday’s concert will also be broadcast live on St. Louis Public Radio and Classic 107.3 both over the air and on the Internet. There’s also a special one-hour “Crafted” concert of the Dukas and Stravinsky works on Friday, March 11, at 6:30 pm that includes drink specials and complimentary snacks starting at 5:30 pm. All performances take place at Powell Symphony Hall in Grand Center.