Symphony Preview: Beyond the sea

By

All good things, they say, must come to an end. This weekend (April 30 and May 1) Stéphane Denève conducts the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra (SLSO) in a program that pays tribute to SLS Chorus Director Amy Kaiser, who is retiring after 26 years (a total of 27 seasons) with the orchestra. She departs on a magic carpet of concert triumphs (including a resplendent Mozart “Requiem” last month) and a wave of fond memories by members of the chorus and orchestra.

[Preview the music with my commercial-free Spotify playlist.]

Appropriately, the evening features two works in which the chorus figures prominently: Debussy’s “Nocturnes” (the third movement features a women’s chorus) and Vaughan Williams’s "A Sea Symphony" for soloists, chorus, and orchestra. It opens, though, with a purely orchestral piece that is getting its third performance with the SLSO since 2020.

|

| Violinist and composer Jessie Montgomery |

That popular piece is “Starburst” by contemporary violinist and composer Jessie Montgomery, whose music has appeared frequently on SLSO programs over the last few years—most recently on April 8-10, when the orchestra gave the local premiere of her “Rounds for Piano and Strings.”

Originally composed for a nine-piece string ensemble and later arranged for string orchestra by Jannina Norpoth, "Starburst" is a delightful sonic explosion that, in the composer's words, refers to "the rapid formation of large numbers of new stars in a galaxy at a rate high enough to alter the structure of the galaxy significantly." To my ears, "Starburst" also calls to mind musical depictions of fireworks by composers like Stravinsky and Debussy while still speaking in a sonic voice that is entirely Ms. Montgomery's own. Rapidly ascending motifs shoot up, expand into musical stars, and then start over again in what the composer describes as "a multidimensional soundscape" that constitutes "a play on imagery of rapidly changing musical colors."

There are plenty of musical colors in Debussy's "Nocturnes" as well, although they’re more like the subtle hues of Impressionist paintings than Montgomery’s sonic pyrotechnics. It consists of three short tone poems (total playing time is around 25 minutes) inspired by literary poems by the symbolist writer Henri de Regnier. The composer wrote a fairly detailed program for "Nocturnes," and rather than attempt to paraphrase it, I'm just going to quote it in toto, using the translation from Donald Brook's “Five great French composers: Berlioz, César Franck, Saint-Saëns, Debussy, Ravel: Their Lives and Works”:

The title Nocturnes is to be interpreted here in a general and, more particularly, in a decorative sense. Therefore, it is not meant to designate the usual form of the Nocturne, but rather all the various impressions and the special effects of light that the word suggests. 'Nuages' renders the immutable aspect of the sky and the slow, solemn motion of the clouds, fading away in grey tones lightly tinged with white. 'Fêtes' gives us the vibrating, dancing rhythm of the atmosphere with sudden flashes of light. There is also the episode of the procession (a dazzling fantastic vision), which passes through the festive scene and becomes merged in it. But the background remains resistantly the same: the festival with its blending of music and luminous dust participating in the cosmic rhythm. 'Sirènes' depicts the sea and its countless rhythms and presently, amongst the waves silvered by the moonlight, is heard the mysterious song of the Sirens as they laugh and pass on.

|

| Women of the SLS Chorus Photo courtesy of the SLSO |

The mysterious song of the Sirens will be sung by members of the women’s chorus. That wordless song is, as Kaiser observes in this weekend’s program notes, “harder for the chorus than it first appears. Stéphane wants a very light, almost innocent sound. It should also be very fluid, like water flowing.”

The aquatic theme continues after intermission with the massive “Sea Symphony”—Vaughan Williams’s first symphony, although he never assigned it or his other symphonies a number. It began life in 1903 (just four years after the premiere of Debussy’s “Nocturnes”) as “The Ocean,” a collection of songs for chorus. By the time it was completed in 1909, it had expanded into a full, four-movement choral symphony in which the chorus is not an add-on but rather an integral part of the ensemble.

“The chorus gets very few breaks,” writes Kaiser in the program notes, and plumbs profound emotional depths. “The symphony is like a farewell to life, and the poetry is so cosmic and deeply felt—it's a very profound piece. I had to figure out how to not be a puddle at every rehearsal!”

|

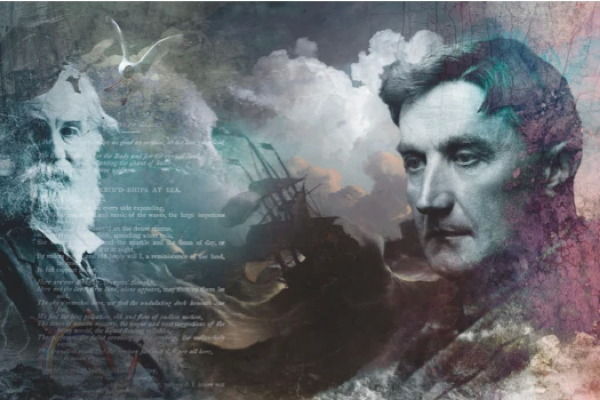

| Walt Whitman from the frontispiece of Leaves of Grass By Samuel Hollyer (1826-1919) of a daguerreotype by Gabriel Harrison (original lost). - Morgan Library & Museum, Public Domain, Link |

Running over an hour, it’s a big, complex piece that calls, in addition to the chorus and soprano and baritone soloists, for a sizable orchestra (including an organ). That could be viewed as surprisingly ambitious for a first symphony. But by the time the “Sea Symphony” had its premiere in 1910, with the the composer on the podium, Vaughan Williams was nearly 40 and no neophyte. He had studied British folk music extensively and had traveled to abroad to study with (among others) Maurice Ravel, which “set VW’s imagination free to roam on the largest scale.” Ravel, he would later recall, taught him “how to orchestrate in points of colour rather than in lines.”

Although the music is strongly shaped by British folk songs, the actual words of the “Sea Symphony” are by the American poet Walt Whitman, from his “Leaves of Grass” collection. Whitman wasn’t well known in Britain at the time, and it was the noted mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell who introduced Vaughan Williams to Whitman’s work. The composer found himself in sympathy with what David Cox (in volume 2 of Robert Simpson’s indispensable “The Symphony”) calls the “unconventionally direct utterance” of the poet. The commanding first movement uses verses from “The Song of the Exposition” and “Song for all Seas, all Ships,” while the ruminative second movement is based on “On the Beach at Night Alone.” The third movement scherzo uses all of “After the Sea-ship” and the lengthy, transcendent finale quotes extensively from “Passage to India.”

I’m assuming the SLSO will use projected text during the concert but if not, the complete lyrics for the “Sea Symphony” are available online. You’ll find this especially helpful if you’re listening to the concert broadcast on the 30th.

The Essentials: The SLSO bids a fond farewell to SLS Chorus Director Amy Kaiser, retiring after 27 seasons, with a program of Vaughn Williams’s “Sea Symphony,” Debussy’s “Nocturnes,” and Jessie Montgomery’s “Starburst.” Stéphane Denève conducts the orchestra and chorus along with soloists Katie Van Kooten, soprano, and Stephen Powell, baritone. Performances are Saturday at 8 pm and Sunday at 3 pm, April 30 and May 1. The Saturday concert will be broadcast live, as usual, on St. Louis Public Radio and Classic 107.3.