Symphony Preview: Darkest before the dawn

By

“The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men,” wrote Robert Burns back in 1785, “Gang aft agley.” Today I might add “and of symphony orchestras as well.”

[Preview the music with my Spotify playlist.]

This weekend, composer/conductor Sir James MacMillan (b. 1959) was originally scheduled to conduct the St. LouisSymphony Orchestra in a program that would have included two of his own compositions: “The World’s Ransoming” for English horn (cor anglais) and orchestra, with SLSO Principal English horn Cally Banham as soloist, and his Violin Concerto No. 2 with Nicola Benedetti, who gave the work its world premiere last fall.

|

| Portrait of Mendelssohn by James Warren Childe (1778–1862), 1839 en.wikipedia.org |

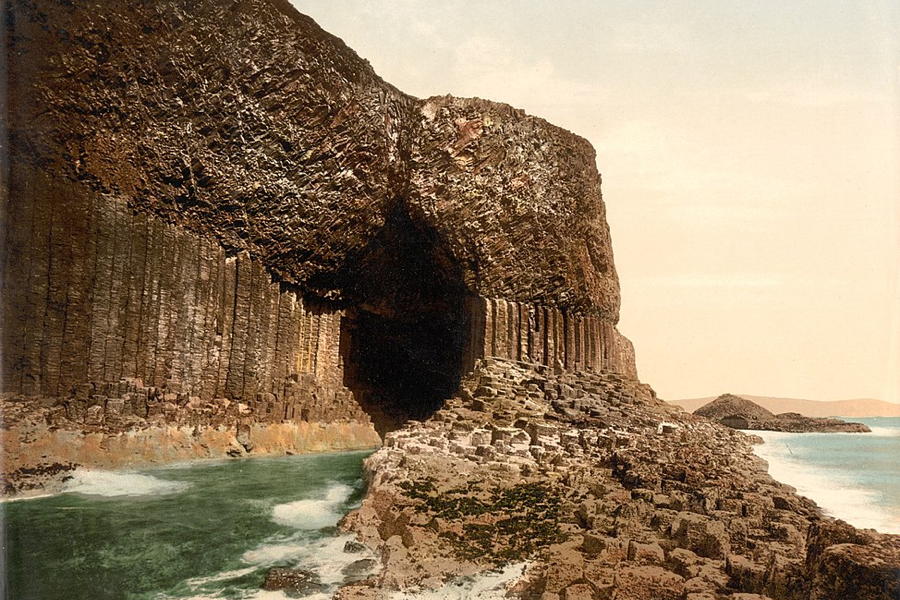

The good news is that Banham is still on the program. The bad news is that Benedetti is not, due to illness. Replacing the concerto will be “The Hebrides (Fingal's Cave),” op. 26 by Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847). Given that both MacMillan and the inspiration for Mendelssohn’s overture are Scottish, that seems appropriate.

Last heard here in 2017, Mendelssohn's overture powerfully summons up the wild and brooding Scottish islands that the composer visited in 1829. His specific inspiration was a visit to Fingal’s Cave on the uninhabited island of Staffa. “With its echoing acoustics, which emphasised the sound of rumbling waves,” writes Hannah Neplova of the BBC Music Magazine, “Fingal's Cave made a deep impression on Mendelssohn, who later sent his sister Fanny a postcard, with the work's opening theme, that read: 'In order to make you understand how extraordinarily the Hebrides affected me, I send you the following, which came into my head there.'”

The actual overture would take three years to write, with the final revised version getting its first performance in Berlin in 1833, with the composer at the podium. Given the overture’s enduring popularity, it looks like it was worth the wait.

The dark and stormy atmosphere of “The Hebrides” turns out to be a good prelude to the musical darkness of “The World’s Ransoming.” Composed in 1995/96 on a commission from the London Symphony Orchestra, it is as the composer relates in his program notes, the first of a series of three works related to the events and liturgies of the Easter Triduum—Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and the Easter Vigil:

The World’s Ransoming focuses on Maundy Thursday and its musical material includes references to plainsongs for that day, Pange lingua and Ubi caritas as well as a Bach chorale (Ach wie nichtig) which I have heard being sung in the eucharistic procession to the altar of repose. The cor anglais part emerges from the orchestra to carry the lamenting ritual through a long, slow and delicately scored introduction and then through a process of metric gear-changes as the music becomes more animated.

.jpg) |

| Sir James MacMillan Photo courtesy of the SLSO |

The title of the work refers to the final lines of Pange lingua (by St. Thomas Aquinas) which describe Christ’s blood “shed for the world’s ransoming.”

The sense of anxiety and lamentation is strong in this music, enhanced by the dark and melancholy sound of the English horn. The piece opens with angry growling sixteenth notes in the low woodwinds that quickly expand to the flutes and brass sections. Violent interjections from the tympani lead to a massive dissonant outburst that quickly subsides to make way for the elaborately melismatic solo line of the English horn. More violent outbursts pop up as well as a weird setting of the Bach chorale for muted brass, wood blocks, and agogo bells that has an unsettling feel of Shostakovich-style mockery.

It all ends with a flurry of sixteenth and thirty-second notes in the woodwinds, a last despairing solo from the cor anglais, and finally, a few measures of whacks on large plywood cubes. The composer says that these “[set] the scene for the next piece in the cycle, the Cello Concerto.” Heard all by themselves, they bring the work to an oddly enigmatic conclusion.

The Easter theme continues after intermission with the “Russian Easter Overture,” Op. 26, written by Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908) in 1888, the same year as his Greatest Hit, “Scheherazade”. Like both “The Hebrides” and “The Ransoming of the World,” this is music that begins in sonic darkness—in this case, the darkness of Passion Saturday, which precedes the unbridled celebration of Easter Sunday, the major holiday of the Orthodox Christian year.

The work is so well-known and so vividly described by the composer in chapter 20 of his autobiography “My Musical Life” (where it title is given as the “Easter Sunday Overture" in the 1923 Judah A. Joffee translation) that I’m going to just refer you there. It’s quite an interesting read, especially the part wherein the composer (who was not a believer) points out that his sonic description of Easter is as much about the holiday’s pagan origins as it is about its importance in the Christian calendar:

And all these Easter loaves and twists and the glowing tapers…. How far a cry from the philosophic and socialistic teaching of Christ! This legendary and heathen side of the holiday, this transition from the gloomy and mysterious evening of Passion Saturday to the unbridled pagan-religious merry-making on the morn of Easter Sunday, is what I was eager to reproduce in my Overture.

|

| Portrait of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov in 1898 by Valentin Serov (detail) en.wikipedia.org |

He went on to add that “in order to appreciate my Overture even ever so slightly, it is necessary that the hearer should have attended Easter morning-service at least once and, at that, not in a domestic chapel, but in a cathedral thronged with people from every walk of life with several priests conducting the cathedral service.” Most of us haven’t had that experience, but at least you can hear a fine performance of it by Yuri Termirkanov and the New York Philharmonic on my Spotify playlist. Or, if you want a closer look, check out the YouTube performance by USSR Symphony Orchestra conducted by Evgeny Svetlanov, which comes with a synchronized score.

Christianity—or at least Dante’s version of it in the “Inferno” section of his “Divine Comedy”—pops up again in the evening’s Big Finish, “Francesca Da Rimini: Symphonic Fantasy after Dante,” op. 32, composed in 1876 by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893). “I wrote it with love and love has turned out pretty well, I think,” he wrote to his brother Modest in October of that year. Audiences have generally agreed; this big, highly charged tone poem is often performed and is well represented on recordings.

Francesca Da Rimini (original name Francesca Da Polenta) was a real noblewoman in 13th-century Italy. The daughter of Guido da Polenta, ruler of Ravenna, Francesca was married off to one Gianciotto Malatesta, whose family ran the show in Rimini, just to the south. As is sometimes the case in marriages of political convenience, this union was not an especially happy one, and Francesca became embroiled in an affair with Gianciotto’s brother Paolo. Giancotto discovered the pair in flagrante delicto and, in a classic display of poor impulse control, murdered them both.

|

| Tchaikovsky circa 1872 en.wikipedia.org |

In the medieval moral universe, this meant that Francesca and Paolo were condemned to the second circle of Hell. In Canto V of “inferno” Dante (in the John Ciardi translation) describes this as:

a place stripped bare of every light

And roaring on the naked dark like seas

Wracked by a war of winds. Their hellish flight

Of storm and counterstorm through time foregone,

Sweeps the souls of the damned before its charge.

Here are “those who sinned in the flesh, the carnal and lusty / Who betrayed reason to their appetite.” This does not, apparently, include guys like Giancotto, who simply betrayed reason for a little casual murder.

But I digress.

Tchaikovsky’s tone poem opens and closes with a vivid depiction of Dante’s “storm and counterstorm” in which strings and winds swirl madly over blasts of brass and percussion. This brackets a lavishly romantic section in which, as in Dante’s original, Francesca tells the story of her ill-fated romance. Dante is so moved that:

I felt my senses reel

And faint away with anguish. I was swept

By such a swoon as death is, and I fell,

As a corpse might fall, to the dead floor of Hell.

Tchaikovsky translates that into an especially violent and impassioned coda, with multiple brass chords and cymbal crashes depicting the poet’s collapse.

The Essentials: James MacMillan conducts the orchestra along with SLSO Principal English Horn Cally Banham in Mendelssohn’s “The Hebrides,” Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Russian Easter Overture,” Tchaikovsky’s “Francesca da Rimini,” and MacMillan’s “The World’s Ransoming.” Performances are Friday at 7:30 pm and Saturday at 8 pm, February 10 and 11, at Powell Symphony Hall in Grand Center. The Saturday performance will be broadcast live on St. Louis Public Radio and Classic 107.3.